Life After Guantánamo: Yemeni Released in Serbia Struggles to Cope with Loneliness and Harassment

5.3.17

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the first two months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the first two months of the Trump administration.

Last week, I posted an article about Hedi Hammami, a Tunisian national held in Guantánamo for eight years, who was released in 2010, but is suffering in his homeland, where he is subjected to persecution by the authorities.

I drew on an article in the New York Times by Carlotta Gall, and I’m pleased to note that, two weeks ago, NPR also focused on the story of a former Guantánamo prisoner as part of a two-hour special on Guantánamo, and Frontline broadcast a 50-minute documentary.

I’m glad to see these reports, because Guantánamo has, in general, slipped off the radar right now, as Donald Trump weighs up whether or not to issue an executive order scrapping President Obama’s unfulfilled promise to close the prison, and ordering new prisoners to be sent there, but the stories of the former prisoners provide a powerful reminder of how wrong Guantánamo has always been, and how much damage it has caused to so many of the men held there.

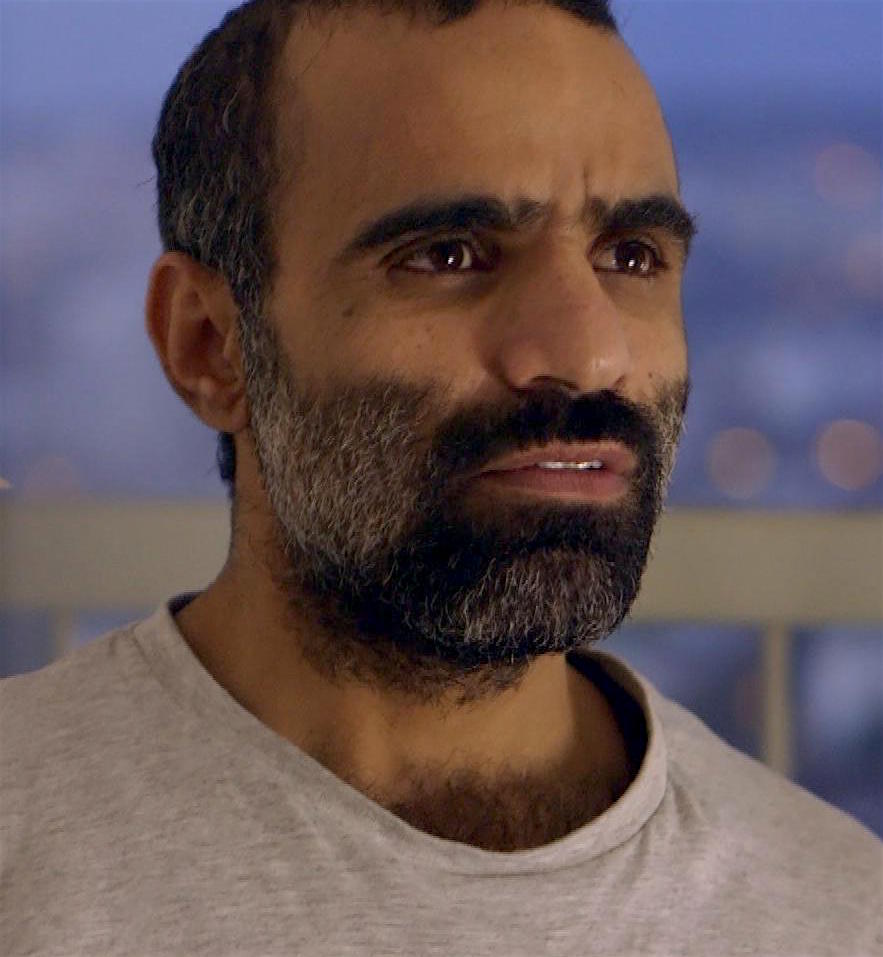

As part of NPR’s coverage, correspondent Arun Rath traveled to Serbia to meet Mansoor al-Dayfi (aka Mansoor al-Zahari), a Yemeni citizen released in July 2016, who was not repatriated because the US refuses to send any Yemenis home, citing security concerns. He was one of 41 prisoners who had been recommended for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial by a high-level task force set up by President Obama shortly after he first took office in January 2009, but who had then been made eligible for a Periodic Review Board, a process akin to parole boards that began in 2013. His case was reviewed in September 2015, and he was recommended for release the month after.

At the time of his review, I described how he had probably been nothing more than “a low-level foot soldier of the Taliban who, in US custody, had become an enthusiastic fan of American culture, becoming a fan of Taylor Swift, Shakira, Game of Thrones (although he felt there was too much bloodshed), US sitcoms, Christopher Nolan movies and Little House on the Prairie, which ‘remind[ed] him of his very rural home with few modern conveniences.’”

Approving his release, the board members stated that they found him “credible in his desire to pursue non-extremist goals and higher education as well as his embrace of western culture,” and “noted his candor regarding his past activities and acknowledgement of mistakes that led to his detention and his willingness to be resettled in a third country and understanding and acceptance of his need for social support after detention.”

He also told the board he wanted to go to college, get a degree in information technology and “marry an educated lovely woman who can be my friend and my wife.”

Instead, however, as Rath explained in “‘Out Of Gitmo’: Released Guantánamo Detainee Struggles In His New Home,” he traveled to Serbia to meet al-Dayfi, finding him in “a sparsely furnished apartment in Belgrade,” which is “small, but with a separate bedroom and kitchen and a living room with a nice view of the city.” Rath noted that, although the Serbian government also set him up with “a monthly stipend and the opportunity for Serbian-language classes,” and, after 14 years in Guantánamo, he was, nominally, free, he told Rath that he felt like he was still in prison.

“When they brought me to Serbia they make my life worse,” he said, adding, “They totally kill my dreams. It’s making my life worse. … Not because I like Guantánamo, but my life become worse here. I feel I am in another jail.”

Frontline’s 40-minute film is available here (and with a transcript here), and I’m also posting it below via YouTube:

Also see below for Arun Rath’s audio broadcast about Mansoor al-Dayfi:

Rath noted that, although al-Dayfi taught himself English at Guantánamo, “he didn’t make it far in his language classes in Serbia,” and explained that “his prospects for an education, a job, a social life and marriage” were all “derailed by the stigma of being an accused terrorist.” He said that he wanted to be sent to an Arab country, and to protest his conditions he embarked on a hunger strike, just as he had at Guantánamo.

As he said, “What I am asking [is] to be sent to another country [where] I can start my life. That [is] what I want, to start a family, start to finish my college education and to live like a normal person. That [is] what I want in my life. Not more. Simple dream … I hope to leave here, where I can start my life, this [is] my hope. Where I can get some support and [go to an]other country where I can least make something of my life, move on with my life, that [is] what I want.”

Arun Rath proceeded to explain that he had come to Serbia “to find out why transferring former Guantánamo inmates deemed ready to re-enter society was so difficult,” and immediately “got a sense of the problem.” As he wrote, “Moments after speaking with Dayfi for the first time, I was stopped by the police and questioned. Even though the Serbian government had agreed to give him a home, it still seemed uncomfortable” with him living in its capital city. Rath actually wrote that the Serbian government “still seemed uncomfortable with an accused terrorist living in its capital city,” but that is an unhelpful description, because al-Dayfi was never credibly accused of having any involvement with terrorism.

Rath noted that he had spoken to officials, up to the Serbian prime minister, who had said that al-Dayfi “was adjusting well,” but that did not seem to be the case. After his first interview, al-Dayfi disappeared. “For two days,” Rath wrote, “he didn’t answer his phone or his door. He then appeared at my hotel, looking terrified, with a fresh bruise on his head. He was certain he had been followed and that we were being watched in the hotel lobby, so we went to my room to talk.”

Rath added, “He told me that the day after our first interview several Serbian men wearing masks had forced their way into his apartment, and pinned him to the floor. While the others searched his apartment, the man holding him down yelled at him, saying things like, ‘If you want to stay here, you have to keep your mouth shut. You are lying. You are playing games.’”

Al-Dayfi told Rath that he “felt humiliated, and he broke down as he told the story.” He said, “They told me basically just shut your mouth and I’m lying,” and added that he had been told, “If you don’t stay in this place, we’re going to take you someplace where you don’t like.”

Rath called this “a difficult situation: interviewing an ex-Guantánamo detainee hiding from authorities in a foreign country, now in my hotel room,” and this was understandable, but it occurred to me that he didn’t reflect on what the Periodic Review Board members had noted — that al-Dayfi had a “need for social support after detention,” indicating that he had some established need of mental health support, which didn’t seem to be being provided to him.

Rath proceeded to discuss al-Dayfi’s background, noting that he was captured in Afghanistan and survived a massacre in a fort (the Qala-i-Janghi massacre, which I have written about extensively over the years), and subsequently “told interrogators he trained with al-Qaida and met repeatedly with Osama bin Laden.” He noted that the US government ended up recognizing that he was actually nothing more than “a low-level fighter who exaggerated his role to sound important,” but Rath was not entirely supportive, stating that he had to ask him that, “if he ha[d] lied about being a terrorist … how could I trust what he said now?”

In response, al-Dayfi told him “he did what he needed to survive,” and proceeded to describe the circumstances in which men at Guantánamo lied. “In Guantánamo, when they put you under pressure, under very bad circumstances you are going to tell them what they want. That’s it,” al-Dayfi said, adding, “Say, like 72 hours under very cold air conditioning, and you are tied to the ground and someone came and poured cold water, whatever. Tell him what he want. Just OK, get out of my skin. I will sign anything, I will admit anything!”

Rath proceeded to explain that al-Dayfi “was in rough shape” when he (Rath) left Serbia in November, and that he was, moreover, “more than a dozen pounds lighter than he had been just weeks before.” He added that he “finally ended his hunger strike in December,” but only “under pressure from his mother, who threatened her own hunger strike if he didn’t start eating.”

He continued to communicate with al-Dayfi, on a regular basis, via video and text, but “he was still miserable.” He told Rath that he “was facing his first real winter without a proper coat,” and, on one occasion, called him “via WhatsApp on a Saturday afternoon, tearing through his apartment and ranting, ‘This is crazy!’” Rath explained, “He was ripping the molding off the walls, yanking out wires, and he pulled out three tiny hidden cameras,” and said, “I’m really, really pissed off. I, this is f****** enough … really it’s enough … being watched on camera in the place where I live.”

Rath continued: “As we were on the call, I saw armed men dressed in black ski masks walk into his apartment. Dayfi switched to the front phone camera so I could watch as they searched his apartment. The men demanded he hand over the phone he was using to record our conversation. Dayfi refused. And after a standoff, some unmasked officials who spoke English arrived.”

“So can you tell me why I’m being watched in my apartment? Give me one reason, am I a criminal?” al-Dayfi asked them. Rath noted that they “didn’t have an answer for him, but demanded his phone again,” to which he responded, “I’m not giving you my phone! No! No, don’t talk to me like this!” By this point, he was screaming at the police. “Don’t scare me,” he said, adding, Look, if I was a bad guy — ” He then “stammered, and spat out in frustration,” as Rath put it, “I’m not stupid. I’m very smart. And very dangerous.”

Rath noted that al-Dayfi’s description of himself as dangerous was, of course, alarming to the Serbs, and asked if al-Dayfi was “a real threat or just a desperate man pushed into a corner?” — a slightly loaded assessment, I thought, as it seemed clear to me that al-Dayfi — a man unanimously approved for release from Guantánamo by a high-level US government review process — was just verbally lashing out in frustration at the way he was being treated.

After telling the officials, as he told Arun Rath, that “he never wanted to be sent to Serbia, he wanted to be sent to an Arab country instead,” Rath noted that one of the Serbian officials told him, “Did you — did you know, uh, that you don’t probably have [the] opportunity to do [that]?” adding that he had been following the story of Guantánamo, and had noted that Trump wanted to send new prisoners there. “Everything change,” he said.

“Eventually,” Rath noted, “there was a sense of resignation in the conversation, and almost humor. The men fell into a very cordial chat for another hour before Dayfi finally agreed to let them take his phone and laptop, which were returned two days later, Dayfi said, wiped of data.”

Rath also noted that Lee Wolosky, the State Department special envoy for Guantánamo closure under President Obama, who negotiated the deal with Serbia to take in al-Dayfi, said that, nevertheless, he “got a fair deal.” As he put it, while failing to acknowledge al-Dayfi’s complaints, “This is a pretty remarkable thing. An individual is picked up as a fighter by the United States. He spends a period of time in Guantánamo. And then one of our partner countries offers not only to take him in, but to give him a stipend, give him an apartment, give him language training, and to provide two years of educational support, as he tries to get himself educated.”

To some extent that is indeed remarkable, but as I look at Mansoor al-Dayfi’s case, I see a man subjected also to a certain amount of harassment, for no good reason, who is also quite significantly alone, in a country without any noticeable Muslim population, and with no one he knows apart from Muhammadi Davliatov, the last Tajik in Guantánamo, who was freed with him., and I understand why he would be frustrated, and why, in the end, he wants to be sent to an Arab country, where he might finally be able to begin to rebuild his life.

Is that too much to ask for?

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

Who's still at Guantánamo?

Who's still at Guantánamo?

28 Responses

Andy Worthington says...

When I posted this on Facebook, I wrote:

Here’s my latest article, looking at a recent NPR story, by correspondent Arun Rath, about the difficulties faced by Mansoor al-Dayfi, a Yemeni released from Guantanamo last July, and given a new home in Serbia. Al-Dayfi, however, is understandably finding it hard to adjust to his supposed freedom: he faces harassment by the Serbian authorities, and quite profound loneliness, as there is no Muslim community to provide him with support, even though the review board that recommended his release in October 2015 noted that he had a “need for social support” after his long imprisonment.

...on March 5th, 2017 at 10:18 pm

Andy Worthington says...

Toia Tutta Jung wrote:

This must be a terrible situation for him.

...on March 5th, 2017 at 10:40 pm

Andy Worthington says...

I know, Toia. The poor man. I hope he will be allowed to go to an Arab country eventually; actually, sooner rather than later.

...on March 5th, 2017 at 10:40 pm

Andy Worthington says...

Toia Tutta Jung wrote:

I hope that too.

...on March 5th, 2017 at 10:40 pm

Andy Worthington says...

Natalia R Scott wrote:

It’s heartbreaking, Andy

...on March 5th, 2017 at 10:42 pm

Andy Worthington says...

Yes, it certainly is, Natalia. I really hope he will be allowed to move to an Arab country, as he wishes.

...on March 5th, 2017 at 10:42 pm

Andy Worthington says...

Natalia R Scott wrote:

I hope so too.

...on March 5th, 2017 at 10:43 pm

Andy Worthington says...

Ann Alexander wrote:

His story makes me very sad, Andy. For a lot of the men released from Guantanamo, their suffering just continues relentlessly.

...on March 6th, 2017 at 4:34 pm

Andy Worthington says...

Yes, very true, Ann. And for Mansoor this is such a betrayal. He was very angry about his imprisonment for the first six years, but then his attorney at the time, who since died, is credited with helping him to become a much more positive person, who then grew to love US culture. yet the US authorities really haven’t done right by him, the poor man.

...on March 6th, 2017 at 4:34 pm

Andy Worthington says...

وضاح الابيني. wrote:

I’m Mansoor. Thank you Andy, my thanks to you all.

It’s hard to move from a prison to another.

I was sold to the CIA for 35000$, and after 15 at guantanamo was forced and sent to Serbia in exchange for 5 millions for Serbian government.

...on March 7th, 2017 at 11:25 am

Andy Worthington says...

Very good to hear from you, Mansoor. I am sure that many of the people who have called for the closure of Guantanamo for many years will also be pleased to hear from you.

...on March 7th, 2017 at 11:28 am

Andy Worthington says...

وضاح الابيني. wrote:

Guantanamo becomes a shame not just on Americans but on all of us. I hope to see that horrible place to be closed and other places like it.

...on March 7th, 2017 at 11:57 am

Andy Worthington says...

I am 100% with you, of course, Mansoor, and I and many other people continue to work towards the day that Guantanamo is finally closed for good – and that no one is tortured by the US or held in any other facility where imprisonment without charge or trial take place. Unfortunately, with Donald Trump now president, we will have to work even harder than before to educate him about the reality of Guantanamo, and why its existence poisons America’s reputation, but we will not give up!

...on March 7th, 2017 at 11:58 am

Andy Worthington says...

Sameera Farouk wrote:

I will be praying you, my brother Mansoor. 🙂

...on March 8th, 2017 at 1:29 am

Andy Worthington says...

وضاح الابيني. wrote:

Thank you sister, I really appreciate your words. We shouldn’t forget those who is still at GTMO.

...on March 8th, 2017 at 1:29 am

Andy Worthington says...

Sameera Farouk wrote:

Jaza Allah khaire, Akhi

...on March 8th, 2017 at 1:30 am

Andy Worthington says...

وضاح الابيني. wrote:

It’s nice of you to support with these kind words, in such place where it is really hard to live especially among these people who look at me like an alien.

I don’t know much about this world and this life any more, 15 years at Guantanamo destroyed everything in my life, and here on this country totally lost, for the last 8 months I have been fighting to get some education, vocational training and whatever can help me to move on with my life but the answer always is “NO, we have a deal just to keep you for two years”.

It’s hard and difficult but with kind people like you and others you give me hope that there are still poeple who haven’t lost their humanity. Thank you all.

...on March 8th, 2017 at 1:30 am

Andy Worthington says...

Sameera Farouk wrote:

Insha Allah, khaire. Dont worry, Allah almighty will help you soon. 🙂

...on March 8th, 2017 at 1:30 am

Andy Worthington says...

I hope it helps you not to feel so alone, Mansoor. There are people thinking about you.

...on March 8th, 2017 at 1:31 am

Andy Worthington says...

Sameera Farouk wrote:

Extremely sad situation, thank you for bringing these terrible human rights violations to our attention. Bless you.

...on March 8th, 2017 at 1:31 am

Andy Worthington says...

You are most welcome, Sameera. Thank you for your interest.

...on March 8th, 2017 at 1:31 am

Iliya says...

To Mansoor: Salaam alaykum wrahmatullah wbarakatuh akhee. I Hope you are in a good spirit and health now InshAllah. Brother, I watched the Frontline about you today, and I was very touched. Do not feel sad No matter what happens, Allaah Test the ones He Loves. I been through a Lot too, so I feel u, believe me. You are in my duaa, and remember you should never feel like you are nothing, because Wallaahi you are a part of this ummah and I am truly proud to be ur sister in Islaam. What are this World akhee? A fading shadow.. So stay close to Allaah and have beautiful sabr, and InshAllah we will be happy in Jannah. Ameen.

...on October 19th, 2017 at 6:22 pm

Iliya says...

And remember something: its great u want to continue ur education again, and move on with life akhee, I admire that after all u been through. But many people are in love with the dunya, or considers what u own, or drive as your worth.. Thats the reality Today of most. But, there are still people, who couldnt care less about wealth and what majority does.. True Worth is imaan and taqwa. Richness of the soul. … Fa tooba lil Ghurabaa. – Ur sister

...on October 19th, 2017 at 6:38 pm

Andy Worthington says...

Thanks for your comments, Iliya. I hope Mansoor gets to see them.

...on October 19th, 2017 at 9:51 pm

Iliya says...

My pleasure, thank you Andy. Do you know how is Mansoor now?

...on October 20th, 2017 at 9:52 am

Andy Worthington says...

You’re welcome, Iliya. Thanks for your interest. I’m seeking some updated information.

...on October 20th, 2017 at 11:58 am

Iliya says...

Please, I Hope anyone would tell him to read my comments, and also I want to offer him some help in terms of money, so he can get warm clothes for Winter.

...on October 20th, 2017 at 11:59 am

Andy Worthington says...

Thanks, Iliya. I’ll get back to you about this soon.

...on October 20th, 2017 at 12:08 pm